Echo

data teaches engineers presentation skills

Echo

data teaches engineers presentation skills

challenge

Create a tech-enabled service student's will be eager to use that improves communication skills.

solution

An online platform connected to a presentation practice space where students can get automated, peer, and expert feedback and a portable system for similar in-class use.

project stats

client: Carnegie Mellon University's Simon Initiativeduration: 8 weeks

role: Project Manager & Designer. I kept the team on track and set milestones. I conducted literature review, interviews, and competitive analysis to explore the problem space. I storyboarded service concepts and tested them with staff members. I created a Wizard of Oz practice simulation for user enactments. I outlined the final presentation. I wrote and narrated the script for the video.

teammates: Neil Bantoc, Vanessa Kalu, Chaoya Lin, Sara Stalla, Min Zhou

research methods: interviews, competitive analysis, literature review, speed dating (needs validation & user enactments)

deliverables: slide deck, demo video, stakeholder map, value flow model, service blueprint, technical analysis

For an idea to shape the world, it must be shared with others. Carnegie Mellon undergrads are excellent at developing these ideas but often lack the acumen to effectively communicate them. Carnegie Mellon easily affords students their first jobs, but sees them struggle to move up the career ladder, as evidenced by salaries that are top in their class right out of school but lackluster mid-career.

Campus leaders from our client, the Simon Initiative, fault the emphasis placed by the school and students on technical competency for displacing the value of soft skills, like communication, which are often not valued in course grading. While various support services exist on-campus, students don’t feel they are personalized or convenient, choosing instead to find an online tutorial or suffer in silence. Our team set out to look at the factors that lead to stunted communication skills to inform potential interventions.

EXPLORATORY RESEARCH

early stakeholder map

narrowing the problem space

We learned about the current landscape through interviews with students, alumni, and staff. We also looked at how peer institutions handle communication skill development, such as career and communication centers, alumni interaction, use of peer review, and the frequency of writing assignments.

We found technical students take a formulaic approach to writing, often failing to include big ideas to form a narrative. Although services exist on-campus to help these students improve, students either don't know about their offerings or yearn for more personalized experiences.

On the contrary, one particularly successful service works with students for whom English is a second language to improve their communication. One course about presenting allows these students to frequently practice presenting in small groups. They then give a final presentation that results in a video recording and detailed instructor feedback. However, there is no similar service for students who are native English speakers or want to improve a specific presentation.

our focus: developing presentation skills in Engineering undergrads

We saw presentations as an area of opportunity ripe for innovation due to a lack of current offerings and ample room for technical and service innovation. An early idea that got us excited about this area was a Vine or Snapchat-like service for broadcasting practice presentations then receiving feedback. We decided to pair our interest in presenting with a focus on Engineering undergrads, as they have limited requirements for communication skill development (a single English course), yet often present design projects in class.

To learn more about this specific need, we interviewed a variety of stakeholders across campus to learn more about engineering students, their program, and current support for the development of presentation and speaking skills.

We found presentations in Engineering courses are evaluated for content but not delivery. There are connections between improving presentation skills and job interview performance. During job fairs and interviews, students speak objectively about their experiences, omitting reflection on their challenges and growth. We learned students will only spend their time at an event or service if it will improve their class performance or get them a job.

Value Flow Model

We looked at everyone who interacts with Engineering students and supports their presentation skills and what is exchanged in each relationship to identify opportunities for reconfiguring the value space.

We looked at how presenting fits into CMU courses. Students can take their presentation to the GCC, but there is not an expert in that area. Outside of the timeline of preparing for an in-class presentation, international students can develop presentation skills at ICC workshops.

CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT & EVALUATION

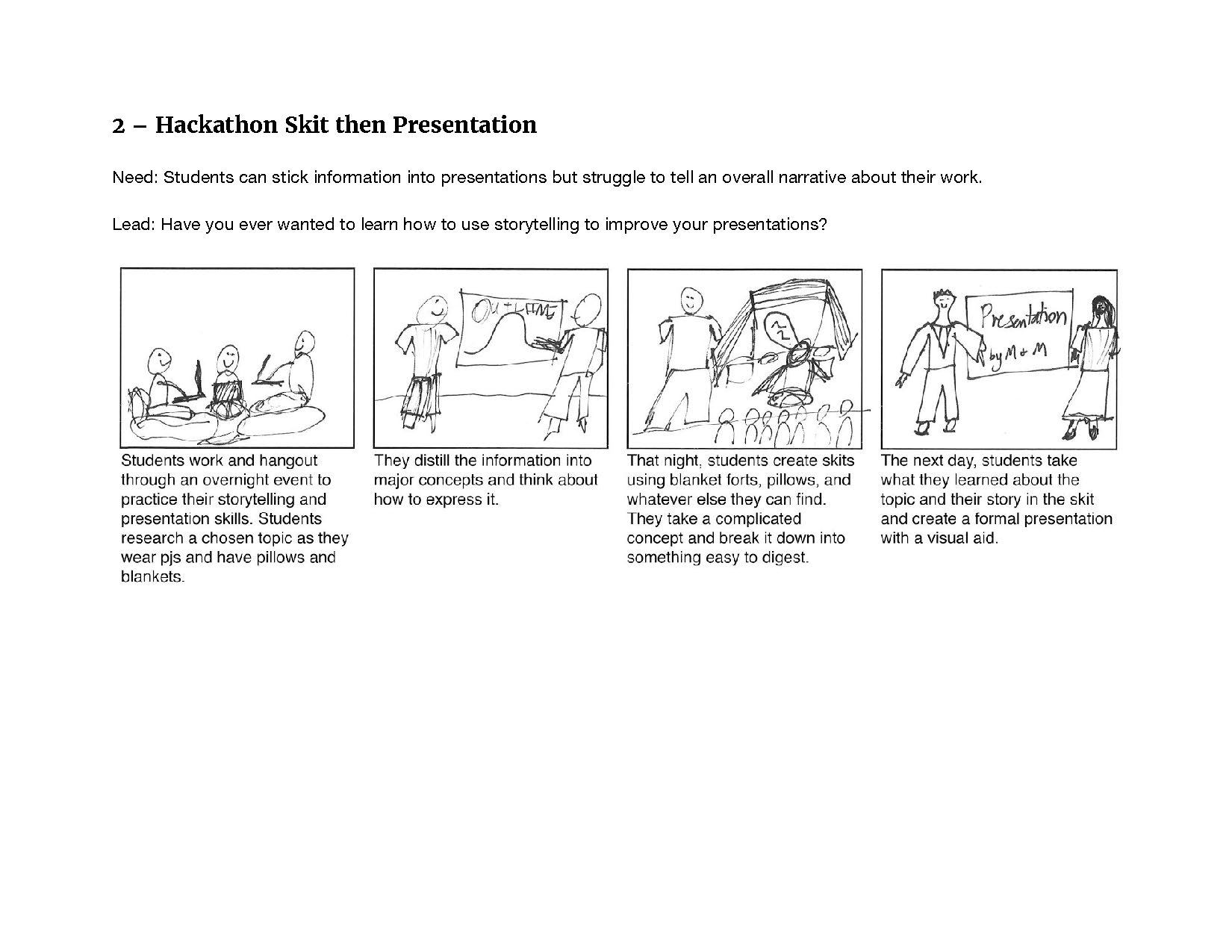

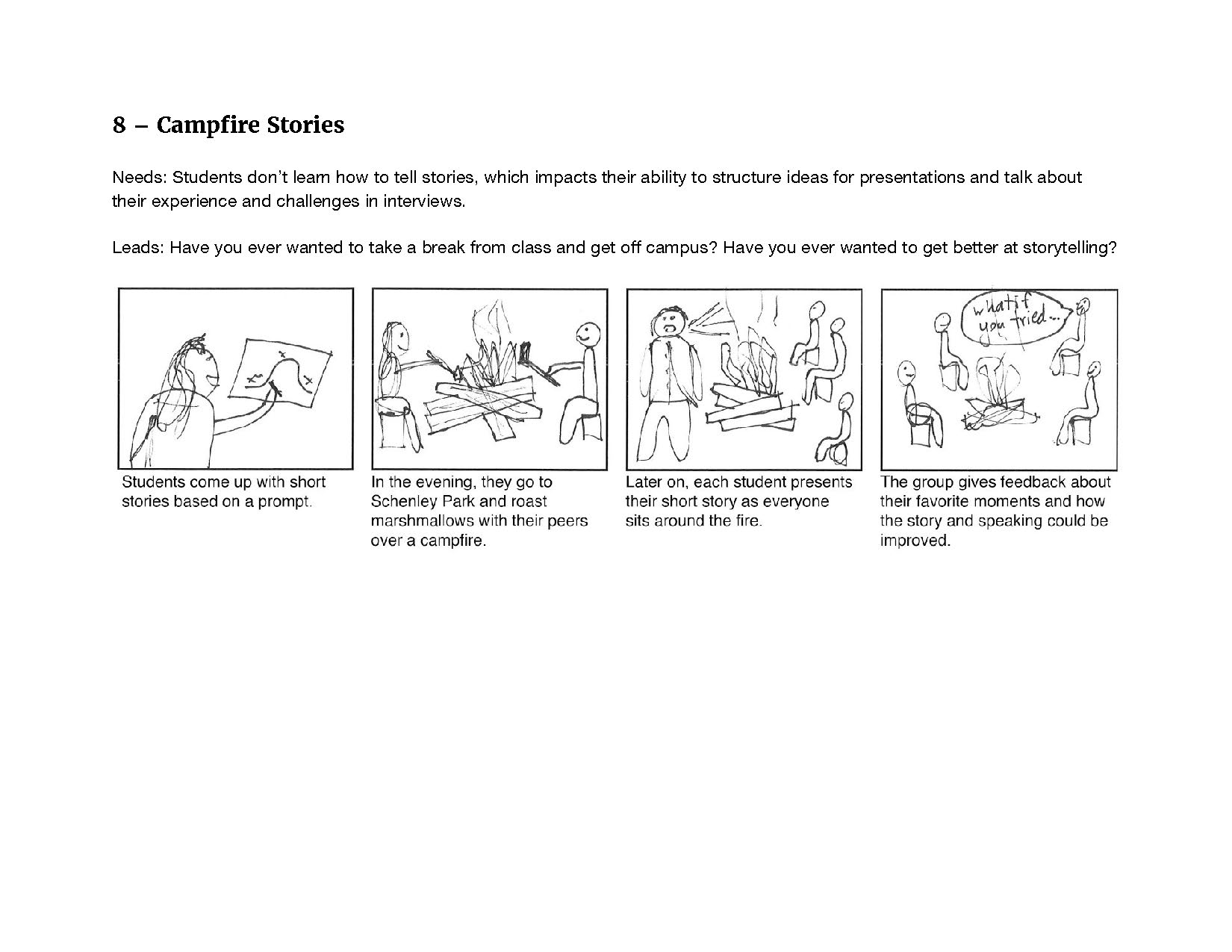

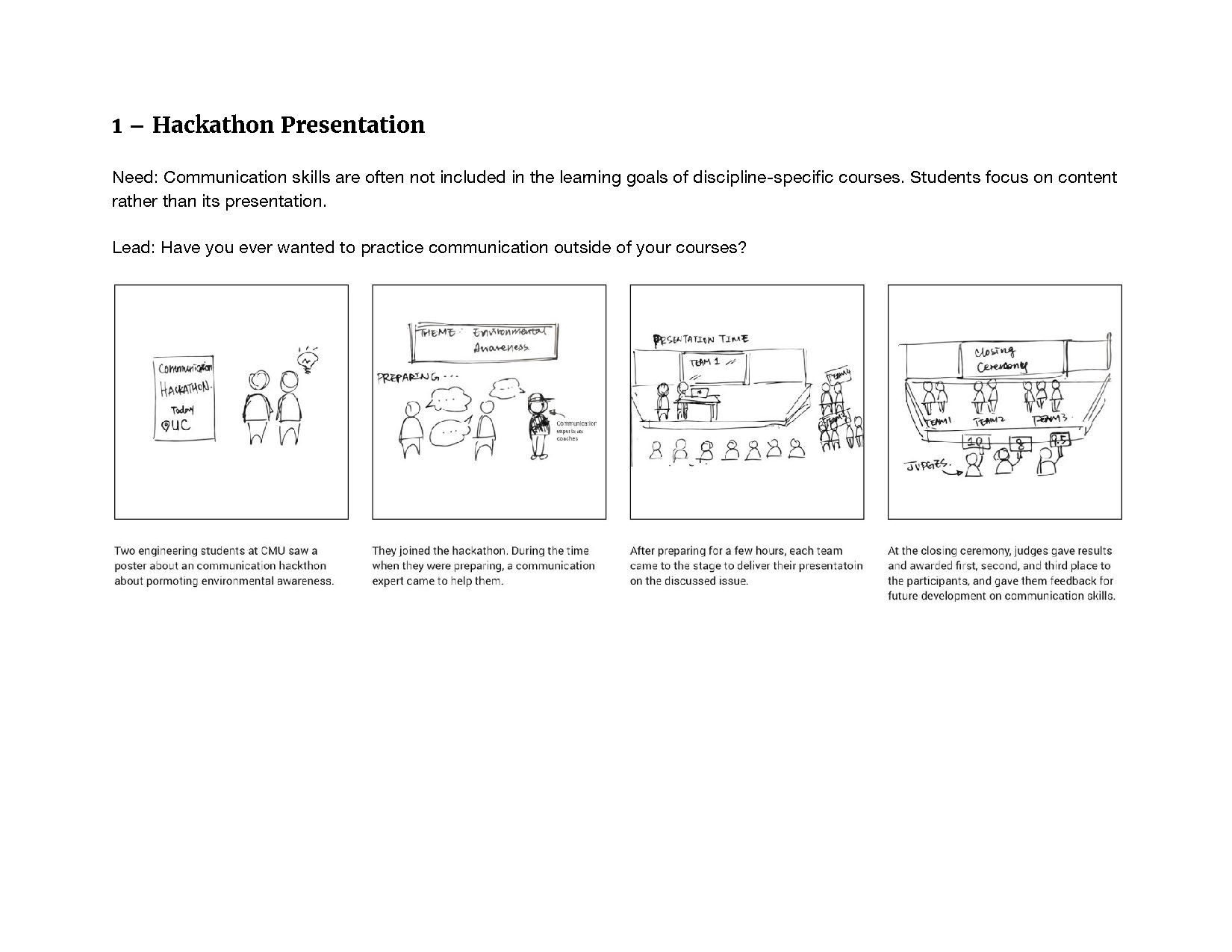

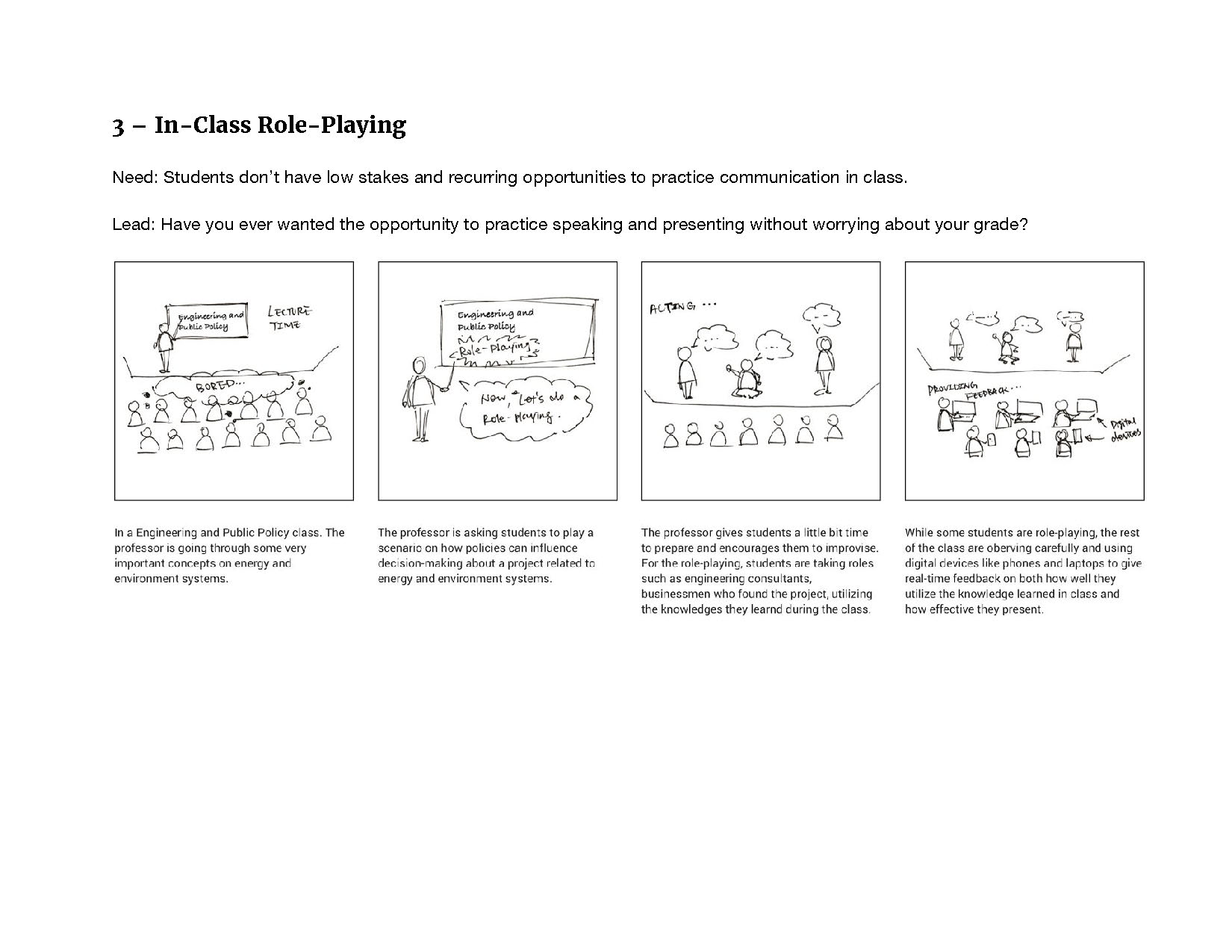

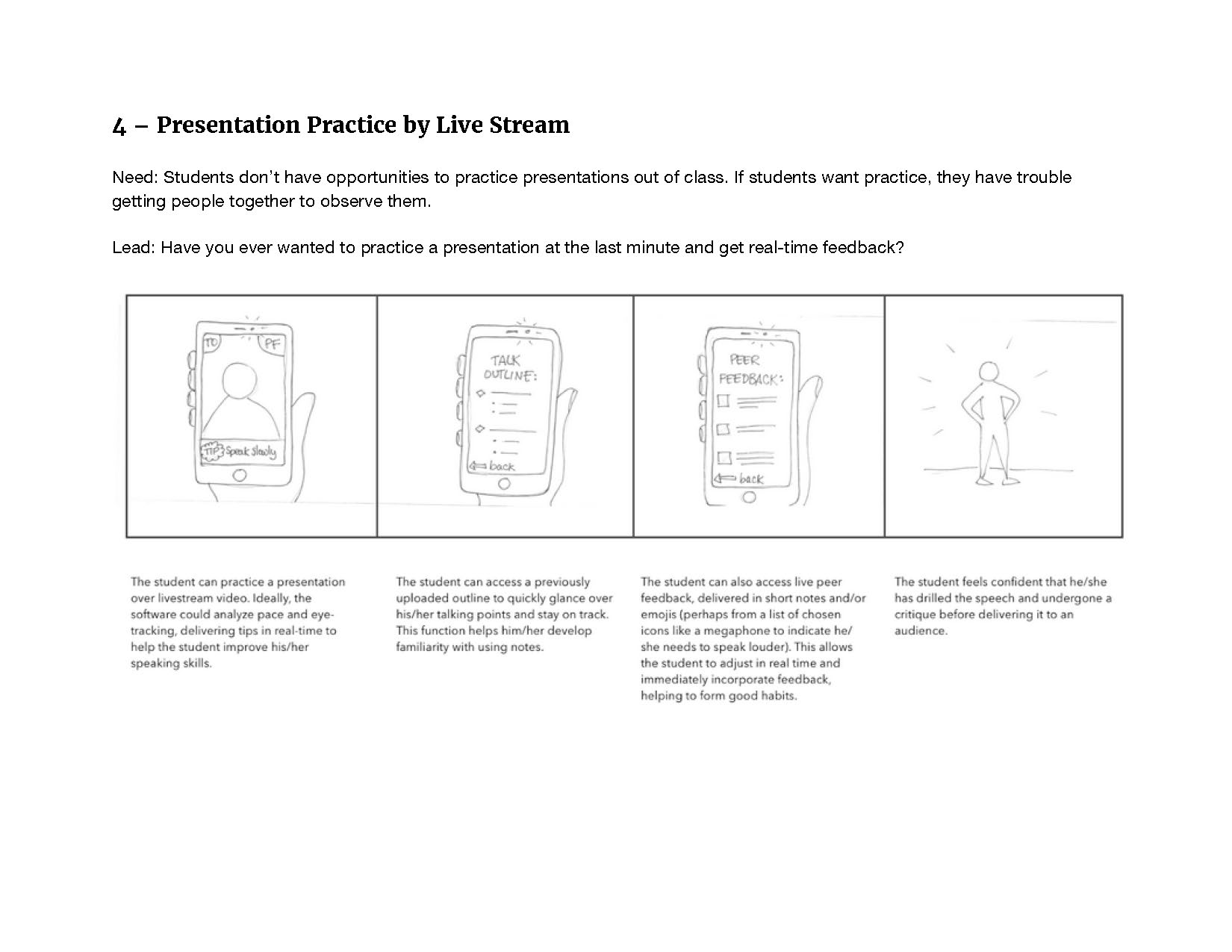

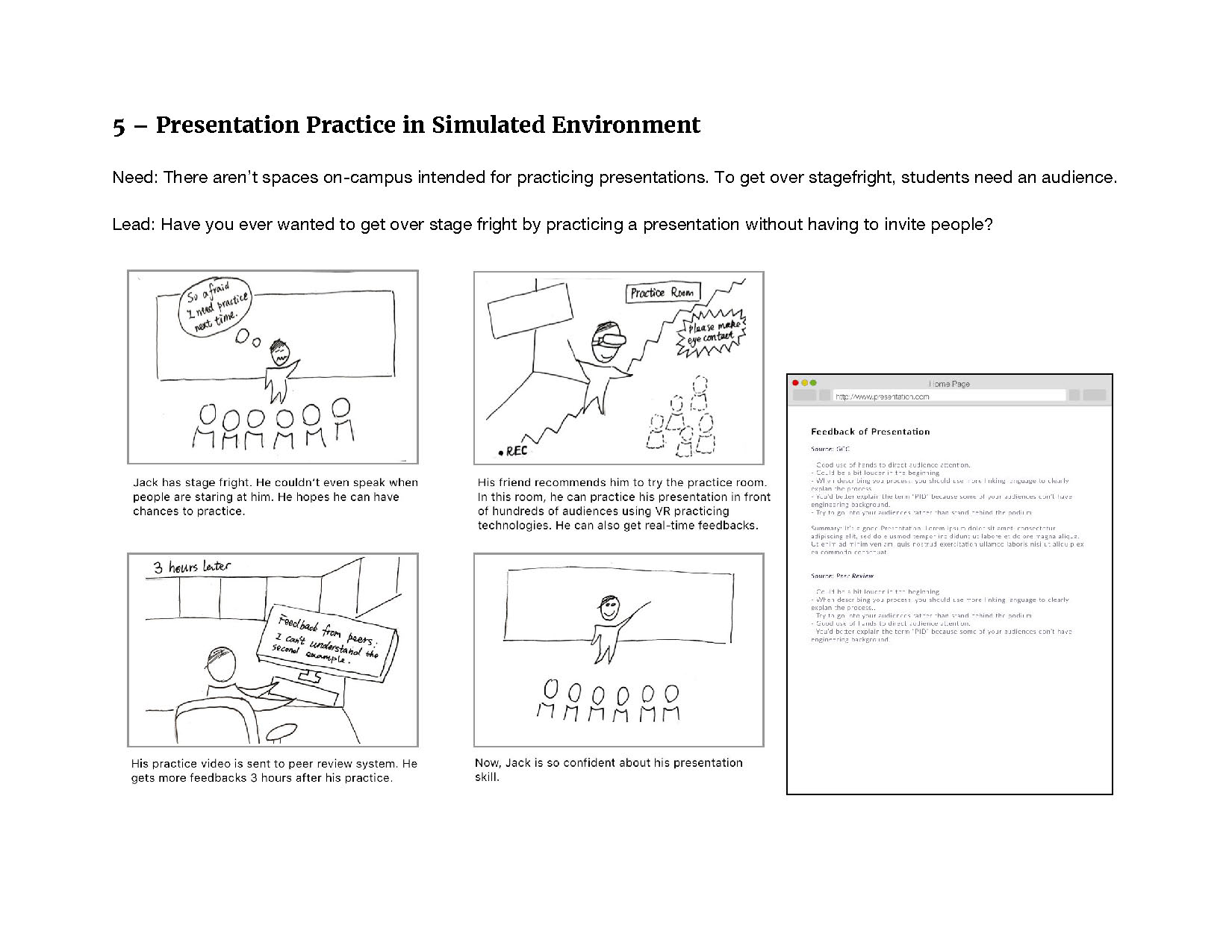

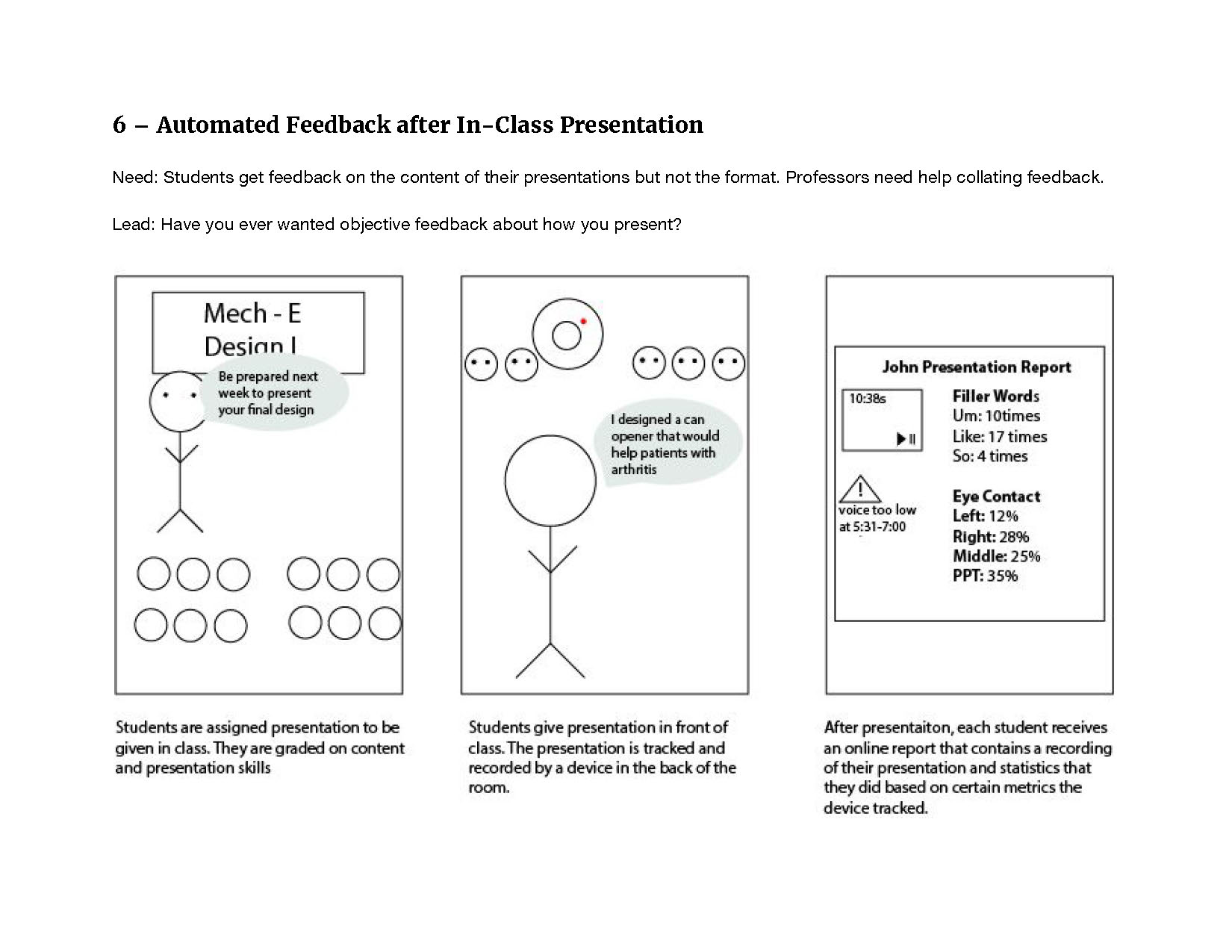

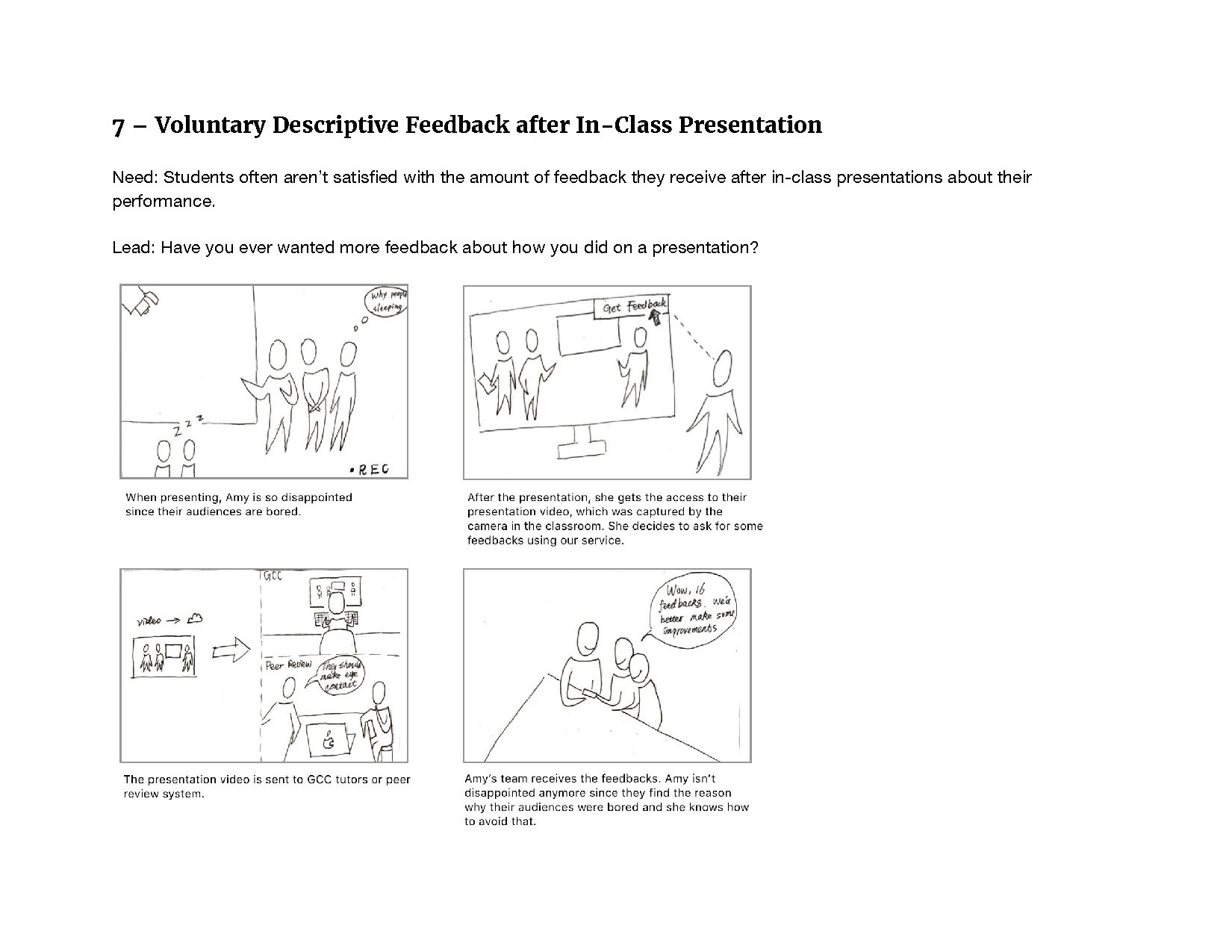

After understanding the current state, we brainstormed potential concepts, deciding to explore these:

storyboarding

We storyboarded out high-level interactions for each idea so we could get feedback from students, staff, and faculty.

speed dating (the nerdy kind)

We used the needs validation technique from the speed dating method to get feedback on the storyboards. Engineering students weren't comfortable with concepts like role playing, which put them in the spotlight. They also weren't willing to spend a full weekend at a hack-a-thon related to presentation skills. Students and staff alike were excited about the virtual practice environment because it's something they were excited to try. The concepts that allowed students to get multiple perspectives using technology were very successful. This led us to focus on a solution that made use of mediated practice and tied in crowdsourced peer feedback.

PROTOTYPING THROUGH USER ENACTMENTS

sample feedback report filled out during user enactment to get participant response

preparing touchpoints

To prepare for the user enactments, we created the artifacts that students would interact with as part of Echo. This included a presentation simulator for the practice space that that used the Wizard of Oz technique to "automatically" analyze participants' presentations and give live feedback. We also made a template for a feedback form that we could fill on the spot and show to participants.

conducting the sessions

We prototyped the practice room experience and the in-class feedback scenario with six students, giving each context for the simulation and asking them to think of a topic. They presented in the conditions of their respective scenario while we recorded metrics and critique. We quickly put this data into a feedback report then discussed it with participants to find out what was most helpful and what could improve.

student gives a practice presentation and receives live feedback

student gives an in-class presentation while researchers ("faculty") and peers record feedback

using feedback to shape final concept

Feedback from our user enactments led us to three factors students found most rewarding about Echo:

Perspective. Students previously had trouble breaking down what makes a presentation successful. Echo's feedback report gives them a framework to recognize and improve these factors.

Layers. Students trust Echo because of its multiple layers of feedback: automatic, peer, and expert. Metrics provide them something objective, peers give them a sense of how their presentation felt, and experts provide credible advice and strategy.

Fast. Students find speed makes Echo a viable tool. Live feedback during practice allows them to improve on the spot. The rapid turn around of the feedback report allows them to give a practice presentation and make changes before class the next day.

We improved pain points that came up during the enactments. Students who struggled with filler words like "uh" were paralyzed each time an alert came up during the simulation. We decided to only display live feedback about factors the presenter could improve in the moment, such as volume or speed. We saved information about more difficult fixes, like addressing filler words, to the feedback report.

GETTING OUR IDEAS OUT THERE

After validating and improving our service, it was time to communicate our solution to the client so they could make it happen.

Artifacts

Stakeholder Map

The efforts of two groups of people must overlap to successfully deliver Echo. Facilitators allow the service to exist by providing funding, administration, and technical infrastructure. Diverse feedback providers from across campus are at the heart of the service, evaluating a presentation's feel and content and advising about delivery. Echo gives students a "high-density" experience because it mobilizes multiple resources and actors in a short amount of time.

Service Blueprint

A service blueprint was the best way for us to convey how the student's journey through Echo interlocked with artifacts and organizational processes. Because our service is delivered across multiple channels, I decided to use this format for the blueprint rather than the traditional five swimlanes.Technical Analysis

To demonstrate the technical feasibility of the automated feedback portion of our solution, we looked at current speech parsing and body language analysis tools, such as Ummo, CMU Sphinx, Microsoft Kinect, and LumoLift.

Feedback

After our final presentation, guests from the Simon Initiative commented that this project is "very CMU" due to its use of technology and data to solve a problem. They agreed students would appreciate this mix of quantitative and qualitative feedback, making an ephemeral act concrete. They immediately asked about the service's operational and development costs, a sign that they want to see Echo exist. The presentation was shared with university leaders who were also supportive of Echo and are looking to build the service and host it within the campus library.

project stats

duration: 1 weekrole: I completed this phase of the project on my own.

deliverables: user story map, storyboards, user flow diagram, paper prototypes

DESIGNING AN ECHO APP

After the course ended, I decided to flesh out the applications necessary for a successful Echo service.

Structuring the Experience

User Story Map

I started by mapping out the activities each role would need to complete.

Storyboarding

I storyboarded the scenarios a mobile app would need to support for a student to use the Echo service.

User Flow

I synthesized the ideas from the storyboards into a rough architectural map of a potential application.

Putting Pencil to Paper

Low-Fidelity Prototyping

I used low-fidelity paper prototyping to quickly get some ideas on paper and work through the flow and layout of the application.

Medium-Fidelity Wireframes

This phase of the project ended with moving some of the paper prototype screens into medium-fidelity wireframes to see how the elements would translate to Material Design.

By the end of this phase of the project, I had a strong sense of the scope and structure of a potential mobile app.